The nineteenth Chopin Competition has come to an end, leaving Warsaw a little quieter than it was a few weeks ago. Every five years, this remarkable event gathers pianists from around the world—young talents chasing perfection and, perhaps, a touch of immortality. For that days, Chopin’s music seems to fill the country’s airwaves and living rooms. In the last edition, his presence in Poland felt even stronger than the pandemic that had just swept through. I was lucky to attend the post-competition concert by the new laureate, the brilliant Canadian Bruce Liu, at the National Forum of Music in Wrocław. It was an evening of pure clarity and joy—a reminder of how alive Chopin’s music still feels when played with honesty and fire.

The Chopin Competition is, for me, also a family story. A story of a musical lineage in which a special place belonged to my grandfather Zygmunt – the very man whose name I carry.

It was his dream that my father would become a pianist. He began playing before the war, as a little boy. In our family apartment on Emilii Plater Street in Warsaw – long gone now, destroyed during the war – stood a piano.

Some photographs have survived… black and white, their edges softly worn, yet still alive with the memory of those moments.

Father played beautifully, by all accounts. He graduated from music school and, in 1960, took part in the preliminary qualifications for the Chopin Competition. He told me about it once – how, at the time, the final decisions were made by teachers from other schools, and how he was instead offered a chance to compete in Brussels.

That year, Polish pianists did not fare well in Warsaw. The brilliant Maurizio Pollini won. Father said with admiration that “no one could match Pollini then,” but he also felt he could have defended the honour of the Polish school.

Something in him must have broken after that. The piano was sold, and in its place appeared a reel-to-reel tape recorder – a technological marvel of the day, of which he was very proud.

Apparently, the look on my grandfather’s face when he saw that massive machine said it all. My father never played again, though whenever he heard a piano somewhere, I could see the quiet ache in his eyes. All that remains of him, the pianist, is one old photograph. And a silence filled with unsaid notes.

There is one more story – also tied to the Competition.

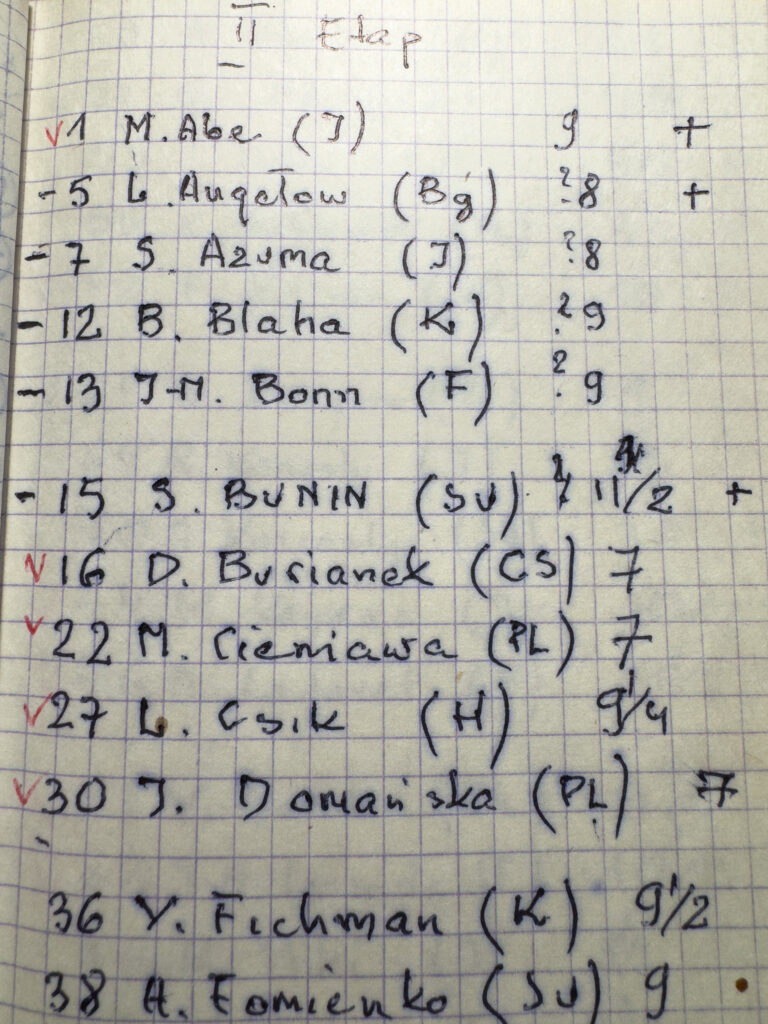

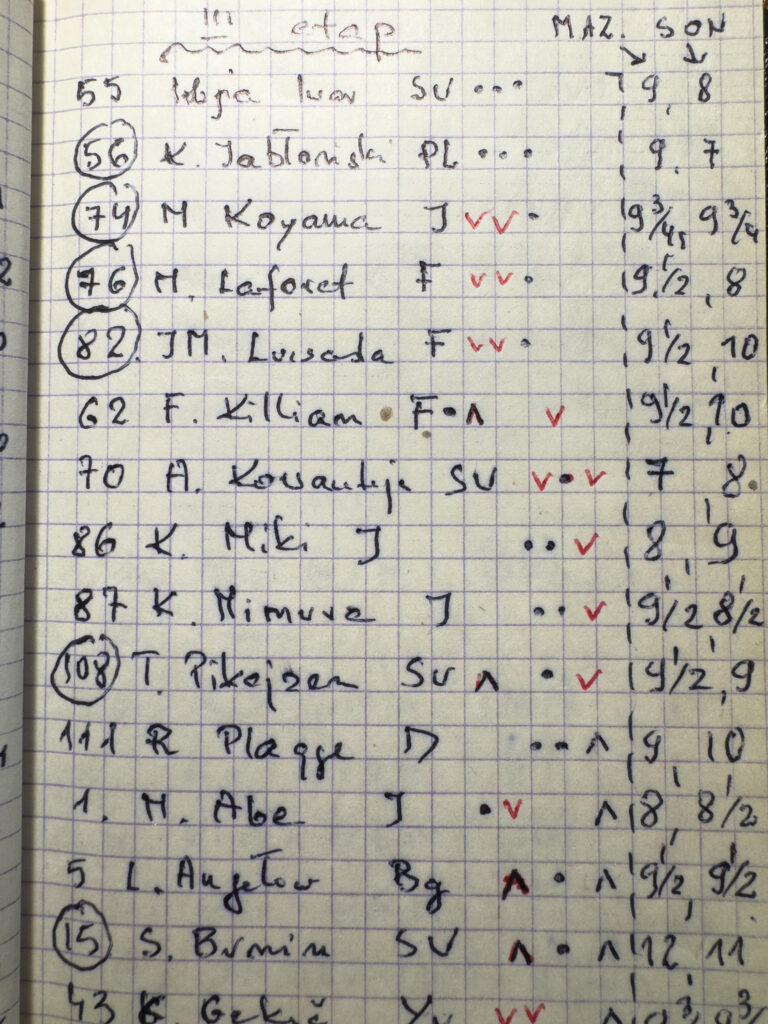

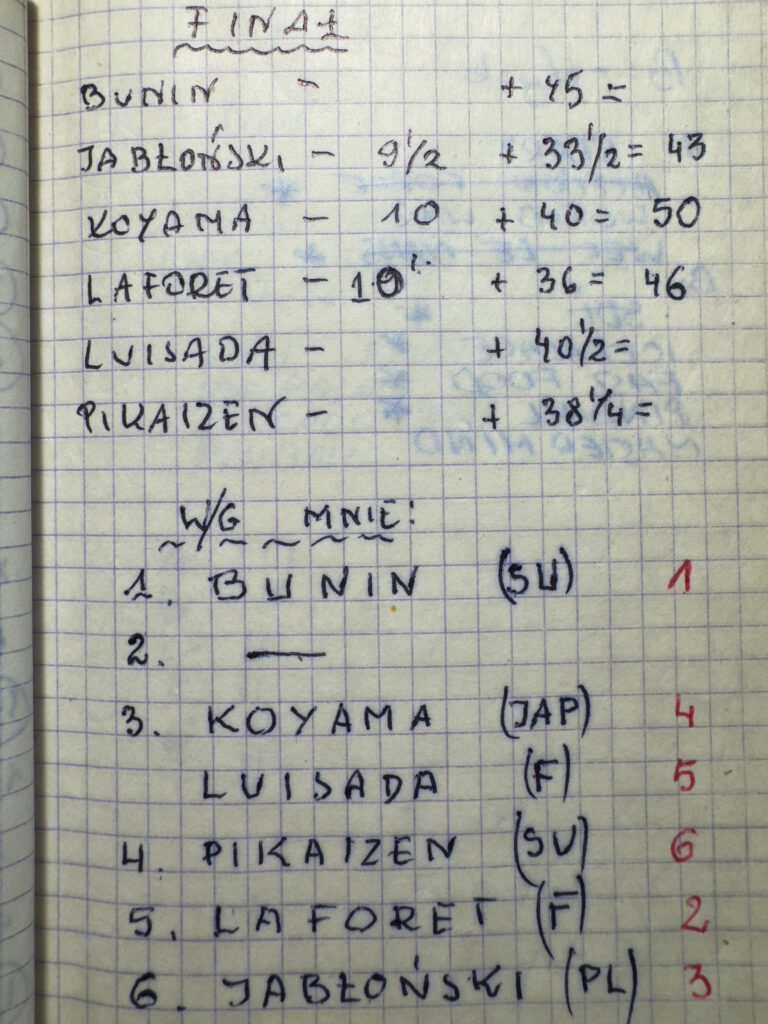

In 1985, my father, by then an accomplished television director, was tasked with supervising the broadcast of two stages of the Chopin Competition. For two weeks he lived in the Metropol Hotel in Warsaw, just ten minutes’ walk from the National Philharmonic.

The Metropol still stands today – I stay there sometimes. It has a certain charm, a whisper of another era.

Back then, Father spent nearly all his days inside the broadcast van, working tirelessly, jotting down small but precise notes in his spare moments. He correctly predicted the winner (fantastic Stanislav Bunin) and most of the laureates – as if he were listening not only with the ear of a professional, but with the heart of a musician he never stopped being.

I don’t play the piano – that was never my choice, more an echo of my father’s dreams.

And yet, Chopin has always been a part of me. His music – filled with light, tenderness, and unrest – awakens something deep inside me. The same kind of tremor I feel whenever my fingers brush a piano key.

My son – Krzyś – doesn’t play any instrument as me. Perhaps that’s all right. Each of us carries our own kind of music inside.

Once, I took a photograph of him that I still cherish. There’s something in it – a trace of silence after sound, a kind of memory that refuses to fade.

But back to the title of this story.

Not long ago, while hiking in the gentle mountains of Lower Silesia, we came across a monument to Fryderyk Chopin on the summit of Orlica.

I admit, I was surprised. The frail, sixteen-year-old Chopin – in the mountains? I had to look it up.

Chopin, it turns out, visited the mountains twice – in 1826 and again in 1829.

In August 1826, sixteen years old, he came to the spa town of Duszniki-Zdrój (then Reinerz) with his mother and sisters, seeking to regain his health. He drank the mineral waters, strolled through the park, and gave one of his first public performances – in the building now known as the Chopin Manor.

There’s no real evidence he climbed Orlica. Yet local tradition insists he took a walk in that direction.

The obelisk standing there today symbolically binds the young composer to this land – more through the spirit of Romanticism than through historical fact.

It’s beautiful, really, how history sometimes writes for a poet or a musician the chapters they never had time to live – or to see.

Three years later, in 1829, Chopin travelled to the Tatra Mountains – to the Chochołowska and Kościeliska valleys. In his letters from that time, he wrote of his awe at the landscape and the mountain folk music:

“I have seen marvellous things. Mountains, valleys, streams – like something out of a fairy tale! But the climbing is hard, so I sit here below, gazing at the peaks others are conquering.”

I like to think that, in that moment, he was simply a young man – like any of us – moved by the beauty of the world, yet wistful that he lacked the strength to touch its highest summits.